In Conjunction with Light: The Plastics exhibition at the Art Gallery of Ontario, 1967

Kirsty Robertson | November 16, 2021

This is part of the Art Museum’s ongoing series of Virtual Spotlights centred on the exhibition Plastic Heart: Surface All The Way Through, organized by Synthetic Collective and produced by the Art Museum where it is on view until November 20, 2021. Click here for details on how to visit the exhibition.

In Fall 1967, the Women’s Committee at the Art Gallery of Ontario arranged the exhibition Plastics, featuring the work of a number of Canadian and US artists.[I] Plastics was billed as the first exhibition in Canada devoted to the theme of plastics in contemporary art, and it was in fact one of the first altogether, beating out dozens of major exhibitions over the next decade[II] that would focus on “exploring the seemingly limitless possibilities in plastic.” Though attracting numerous well-known artists ranging from Joyce Wieland to Claes Oldenburg,[III] and from Les Levine to IAIN BAXTER&, the fact that the exhibition was organized as a fundraiser by the Women’s Committee, and held in the Art Rental Gallery in the basement rather than a traditional gallery space, seems to have blinded AGO’s administration to its importance and innovation. Looking back at this exhibition from 2021, what was it about plastics that drew the attention of the Women’s Committee? What did they learn about plastics through their research? And what can we glean today from their initial investigations and work with artists?

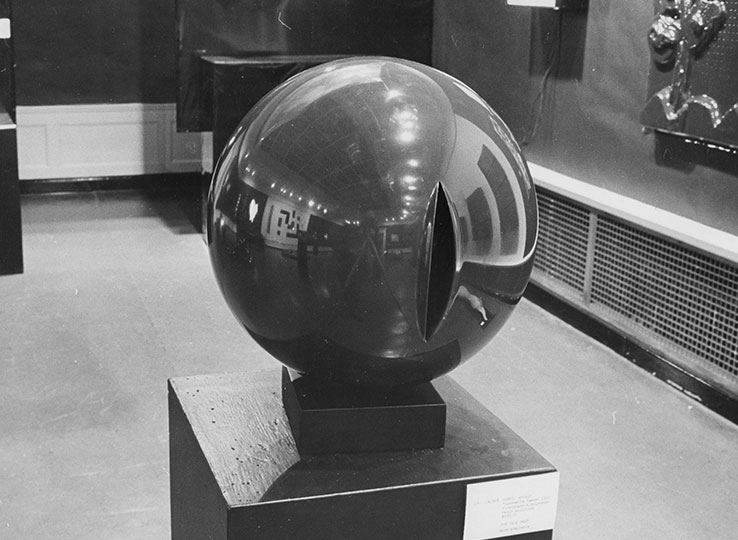

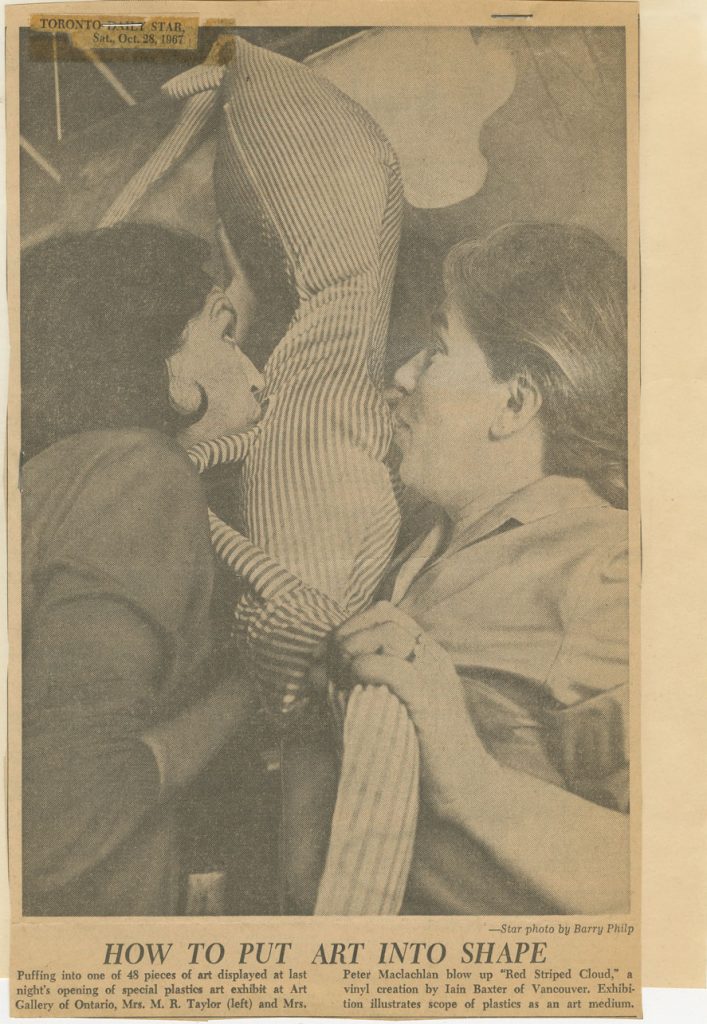

Plastics opened October 28, 1967 and ran only until November 14. Plinths were painted black and installed at different heights throughout the relatively small space—creating a stripped-back, modernist look that would have highlighted the vibrant colours of many of the works, now visible only in the glossy black and white documentation of the show. In the exhibition, plastic is celebrated for its flexible structural framework; one of the committee members wrote of it: “a new definition of space without solids … a space which tantalizes the eye with puzzling depths and projections and reveals inner and outer surfaces simultaneously. Light both reflected and refracted plays an essential part in revealing form.” Despite a dim reception from gallery administration—a letter sent from the Women’s Committee to William Withrow, Director of the AGO, notes that the exhibition time was almost halved at the last moment, largely because a crew of preparators were shifted away from the Art Rental Gallery to other exhibitions—Plastics was enthusiastically received by the public. A raucous opening night, complete with several members of the Women’s Committee wearing plastic dresses designed by John Burkholder, signalled the growing popularity of such art works. Wrote one reviewer: “This exhibition completely refutes any idea that there can be no such thing as plastic art.”[IV] Indeed the popularity of the works—and the crowds in the cramped rental space—resulted in several sales, but also in the damage and theft of a number of the works.

Unlike some of its counterparts, such as US-based exhibitions like the traveling 1969-70 A Plastic Presence, the lasting impact of Plastics is hard to trace. There is little to no mention of the exhibition in articles on 1960s art in Canada, nor is it referred to in histories of new media exhibitions. And yet the archive is a treasure trove. Not only does it include interviews with a number of early adopter artists, documenting both their successes and failures with new materials, it also captures the astounding amount of volunteer labour that went into the exhibition, and the steep learning curve involved in understanding plastics. Moving from house to house, the women—led by Marie Fleming (who would later become a curator at the AGO) and Jeanne Parkin (who would also become a curator, gallerist, and run an arts management firm)—organized every aspect of the exhibition from contacting the artists and securing the loans to “deliver[ing] a cake to the basement staff with a note of thanks for their efforts.”

From the initial suggestion of a show on plastics almost a year prior to the opening, the committee gleaned and shared information, quickly realizing that they had taken on a peculiarly complicated topic. What even is plastic? “A plastic can be broadly defined as a substance which, though solid in its finished state, is, at some point in the process of manufacture, sufficiently fluid (or plastic) to be formed into various shapes, usually through the application of heat and/or pressure,” wrote an anonymous committee member.[V] The notes document the chemical makeup of plastics, the differences between thermosetting and thermoplastics and different examples of each in the chosen works for the exhibition. The properties of plastics are discussed alongside the ways they can be manipulated to be experienced as “transparent, translucent, opaque, thick shapes, thin planes, tubes, etc., in conjunction with light and so on.” Eventually the writer concludes: “It requires considerable discipline not to be carried away by the fascination and sensuous beauty of the materials themselves.” Plastics also, the document insists, alter the relationship between artist and work. For the most part, using plastics involves the artist working in an urban location and building a relationship with industry; no longer can the artist work alone in the studio. In turn this meant that with a few exceptions (Les Levine’s Disposables, which were priced in the show at $8 each) works in the exhibition would be quite expensive, even though “plastics are so widely available, used so much in throw away packages and so on.” An interview with exhibiting artist Michael Hayden goes into further detail, noting the need to create blueprints and models, pay plastic fabricators and occasionally consult with chemists, pay to use the “I.B.M. computers” for large calculations in an era prior to personal computing, and the cost of fragile materials that needed to be replaced if broken. For artists like Hayden, working on new formulations and new ways of experimenting with colour and materials, plastics were both exciting and prohibitively expensive.

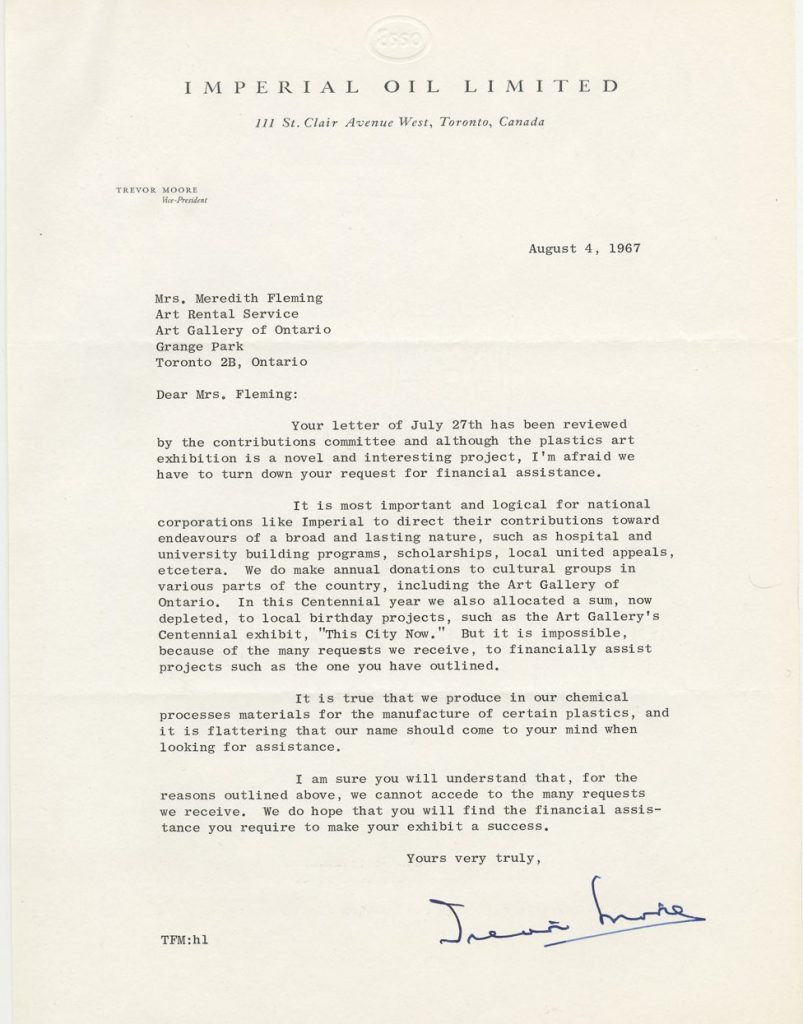

In Plastic Heart: Surface All the Way Through, we have included an artefact from the 1967 Plastics exhibition, a promotional poster printed on opaque polyethylene sheet plastic. Dow Chemical, DuPont, Eastman Kodak, Union Carbide, C-I-L, and Imperial Oil were all considered for potential sponsorship. Only Union Carbide came through, providing the material on which the invitation and posters were printed. In the sponsorship invitation to Union Carbide, the Committee notes: “The exhibition, we hope, will be an exciting and provocative first. It will include advanced work in the medium of plastics. It should contribute to the breakdown of barriers between commonplace and fine art materials, and encourage an appreciation of plastics as a material with a beauty of its own.”

While the pitch to Union Carbide may have focused solely on the seriousness of plastics as an artistic medium, the complexities of plastics are front and centre on the poster, which includes quotes from many of the artists involved in the show. For the most part, artists document their love of the new material, the way that it allows them to explore space and illumination. But already, Michael Snow is quoted noting, “It’s interesting to see how plastics age very badly. They’re so innocent when young.” And Joyce Wieland (one of the few women artists in the show) lays bare the compromises demanded by plastics: “The same corporate structure which leases napalm to responsible groups at reasonable rates gifts you with inexpensive fun things made of plastics. Plastic dishes are known carcinogens. Unbacked vinyl is my medium. The blues were considered low. I love you.” And while he is not quoted on the poster, in the longer interview Hayden discusses the toxic properties of plastics, noting “The odiforousness of plastic was the major reason why I left home and found a studio. I now use a gas mask whenever I spray my plastics.”

Plastics was an exhibition ahead of its time. In short, while the show focused on the possibilities of plastics as an art material and celebrated those potentials, and while sponsorships from chemical and oil companies were sought to uphold a then commonly-held position on the positive relationship between oil, chemicals, plastics, and art, artists were simultaneously well aware of both the potentials and pitfalls of the material. As Plastic Heart demonstrates, the damage wrought by plastics is closely tied to their allure, both in terms of ubiquity and convenience (which are repeatedly mentioned by the Women’s Committee) and indeed, their lusciousness and elegance. As the Women’s Committee would find, plastics are a conundrum, both seductive and damaging.

Endnotes

[I] Much of the information in this article comes from the following file at the E. P. Taylor Library and Archives, Art Gallery of Ontario: Women’s Committee and Junior Women’s Committee Record Series, Subseries 4: Art Rental Service, Final A Exhibition and Programming Material, 1967-1978, BOX 57 and Subseries 3: Exhibitions, 1965-71, BOX 52. For more on the role of volunteer women’s committees in Canada, see the work of Anne Whitelaw, Lianne McTavish, and Irina D. Mihalash.

[II] The only plastics-dedicated exhibition I’ve found that opened earlier was Plastics, John Daniels Gallery, New York, 1965. A second exhibition called Plastics West Coast was held at the Hansen-Fuller Gallery, San Francisco in the same year as the AGO exhibition. Sculpture 67, which was held at Toronto City Hall from June 1-July 17, 1967 included work by many of the artists in Plastics, but it was not specifically dedicated to the material.

[III] The Claes Oldenburg Tea Bag multiple included in Plastic Heart was also shown in the Plastics exhibition. We are unsure if it is the same edition of the work.

[IV] Kaaren Blatchford, “What, plastic art?” The Telegram (Toronto) (November 4, 1967), p. 37.

[V] The texts in this paragraph appear to be from a draft essay that was planned for a brochure to accompany the exhibition. Ultimately, the text was cut down to a single paragraph and printed on the poster. The brochure was not produced due to cost.

Credits

Banner Image: Exhibition Opening, Plastics, October 28 – November 14, 1967. Organized by Art Rental (Women’s Committee), Art Gallery of Ontario. LA.165208. Courtesy Edward P. Taylor Library and Archives. Photo © AGO.

Image 1: Installation view, Arthur Handy, Aphrodite Yawns, 1967, from Plastics, October 28 – November 14, 1967. Organized by Art Rental (Women’s Committee), Art Gallery of

Ontario. LA.165210. Courtesy Edward P. Taylor Library and Archives. Artwork © Arthur

Handy. Photo © AGO.

Image 2: Installation view, Plastics, October 28 – November 14, 1967. Organized by Art Rental (Women’s Committee), Art Gallery of Ontario. LA.165209. Courtesy Edward P. Taylor Library and Archives. Photo © AGO.

Image 3: Imperial Oil Limited Letter to Mrs. Meredith Fleming, Art Rental & Women’s Committee August 4, 1967. LA.165206. Courtesy Edward P. Taylor Library and Archives, Art Gallery of Ontario.

Image 4: Toronto Daily Star, Oct. 28, 1967. “How to put art into shape”, Review of Plastics exhibition. LA.165207. Courtesy Edward P. Taylor Library and Archives, Art Gallery of Ontario. Toronto Star via Getty Images.

Virtual Spotlight developed by Daniella Sanader, Content Curator, Plastic Heart: Surface All the Way Through.

About

Kirsty Robertson (she/her) is Associate Professor of Contemporary Art and Director of Museum and Curatorial Studies at Western University, Canada. Robertson has published widely on activism, visual culture and museums, culminating in her book Tear Gas Epiphanies: Protest, Museums, Culture (2019). Robertson is a founding member of the Synthetic Collective, project co-lead on A Museum for Future Fossils (an ongoing “vernacular museum” focused on responding curatorially to ecological crisis), and Director of the Centre for Sustainable Curating at Western University.