The Stories We Tell Ourselves Are Killing Us

Christina Battle | November 11, 2021

This is part of the Art Museum’s ongoing series of Virtual Spotlights centred on the exhibition Plastic Heart: Surface All The Way Through, organized by Synthetic Collective and produced by the Art Museum where it is on view until November 20, 2021. Click here for details on how to visit the exhibition.

Disaster: The complex combination of hazards and social factors that lead to destructive results.[I]

In early 2019, I visited Edmonton’s Waste Management Centre and, along with my mom, participated in one of their guided facility tours. We began in a small lecture room, where the guide (a Public Education Specialist) asked us what questions we had going into the tour. Our group was small: there were eight of us, and I quickly learned more about each of the participants. Two were in charge of their local company’s recycling program; a woman (along with her preteen daughter) was starting up a business and wanted to more information about how recycling might play into her packaging; and two men, one translating for the other, were touring the site as their company was considering partnering with the Edmonton facility. When the men explained that they were interested in purchasing plastic waste from Edmonton in order to transform it into microplastics in China, our tour guide made sure to let us know we were in for a treat. Having such interests along for the tour, he ensured us, would offer a great opportunity to have first-hand insight into the overall process of plastics recycling.

Perhaps because of this unique amalgam of participants, it quickly became clear that capitalism sits at the centre of our recycling capabilities. Only those plastics that can be sold within the market are taken on at the site; the rest remain relegated as garbage. Our guide helped reiterate this fact along every stop of the tour, often asking the men from the microplastics plant in China to help prove his point: Could you turn this type of plastic into something else at your plant? Most often they’d respond: No. The woman looking for advice for her new package designs made her primary concern clear. She was keen to know where this packaging might end up after use, and wanted to develop a strategy that would have minimal impact on the environment—and she never seemed satisfied with the answers to her questions.

As the tour wore on, the woman frustratedly asked for a direct answer: What sort of material should she use in order to produce the smallest amount of plastic waste? Our tour guide again reiterated that the question was complex. The best way, he reminded her, was to not use plastic at all. That seemed impossible for her to consider, so instead, she began speaking directly with the Chinese businessmen. They suggested the material that their plant utilized and she was satisfied—great, she’d just use that, then. Our tour guide asked if she had considered the resources expended by shipping her waste to China as part of her recycling goals; what about the labour concerns regarding those who might work within the Chinese plant? Maybe considering wages and labour standards of the sites she was relying on should also factor into her decision making, he prompted. By this point she was either ignoring him or had given up: she had come in search of a simple answer and was unwilling to accept anything else.

A year after this tour, I was invited by the Synthetic Collective to research the relationship between plastics and COVID-19. I monitored how online conversations around plastic were evolving across the pandemic, and my final report—Public perceptions of plastic during the start of COVID (May thru August 2020) as witnessed on Twitter; and thoughts on strategies for moving forward—was filed at the end of that summer.[II]

My report put forth a number of conclusions: “one of the biggest problems with public perception around plastic during the COVID crisis has been the flattening of different types and uses into one category. […] Issues contributing to the complexity of the perception of plastics include: a misunderstanding of the difference between single-use and medical plastic; a lack of knowledge regarding the reality of recycling capabilities and processes; and the absence of public conversation surrounding the overall health impacts of the plastic production industry.”[III]

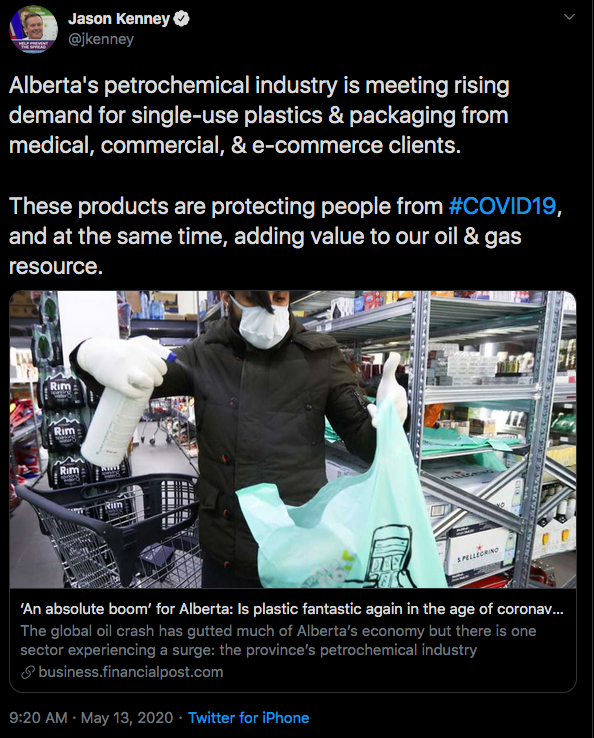

From this research, I isolated the dominant online conversations across those four months in 2020. Here, I will focus on the push to use plastic bags and plexiglass shields across the pandemic. These conversations quite incorrectly reinforced the idea that plastic was the only safe option against viral spread. The narrative took hold quite quickly both online and off, and it was based on disinformation pushed by the plastics industry.[IV]

Going into this research, I knew that our relationship with plastic was complex, but I was still surprised by how the conversation unfolded online. I was struck by how far we remain from truly understanding much of the issue. From my research report:

Our relationship with plastic is obviously already fraught in a number of ways, but I wonder if it might come down to this sense we have that plastic = clean; plastic = safe; plastic = secure; and our inability to separate the larger issues of waste from the various types of plastic. This was particularly acute because of the nature of the COVID crisis itself, and I wonder if working to help tease apart this particular thread might lead to working solutions.[V]

The stories we tell ourselves are powerful, and with propaganda from the plastics industry dominating our newsfeeds, our ability to collectively understand plastics waste has yet to manifest. We’ve created a narrative around recycling that is dominated by fantasy, and even though it might help us to feel more comfortable with the problem, we’re far from ever solving it. Ultimately: “This comes as no surprise to those who work on the issue. For decades, the plastic industry has been trying to convince the American public that their products are recyclable. But behind every magician’s disappearing act is a trap door, and behind every company’s insistence that plastic is recyclable is another trip to the landfill, or another scheme to use public funds to pursue harmful and unviable technologies.”[VI]

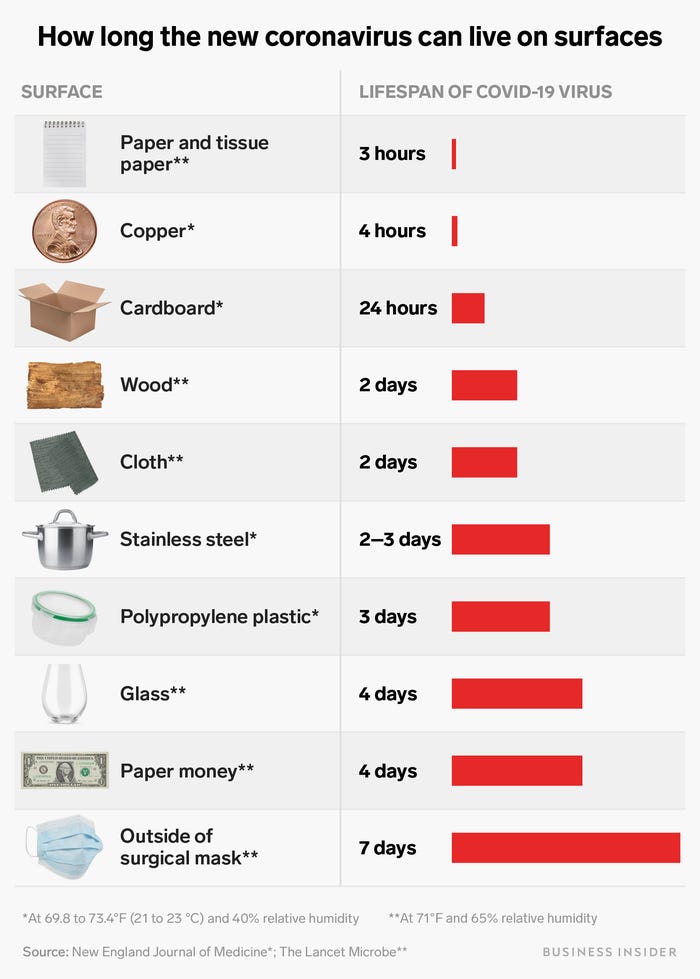

In mid-April 2020, a month after a number of provinces had already declared states of emergency due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and when over a thousand Canadians had already been killed by the virus, a study came out from the New England Journal of Medicine looking at the stability of SARS-CoV-2 on various materials.[VII] Their findings showed that the COVID-19 virus was more stable on plastic than on a number of other materials including paper, copper, cardboard, and cloth.[VIII]

Reading this report struck me: at the time, many grocery store chains across the country had refused recycled or fabric bags in favour of single-use plastic ones, even though, in many cases, plastic had previously been be banned. I struggled with the realization that the stores had done this without tangible evidence to back up the decision. Looking back at the timeline, I discovered that the Federal Government never weighed in on the use of grocery bags during the pandemic, although a small number of provincial governments did around the time that many stores were re-introducing plastic.[IX] It seemed that the stores were responding to the narrative being shaped across public discourse—heavily influenced by the PR machine of the plastics industry—that plastic was the safest choice against the virus.[X]

I’m most struck by how quickly the narrative of “plastic = safe” was spread and taken up: how quickly everyone went along with it, and how easily everyone believed it. Given how quickly COVID-19 took over in spring 2020, and how many unknowns there were at the time surrounding the virus (and still are), I understand the need to feel like people were taking some kind of action to help keep communities safe. But in this case, the rapid reliance on plastic across the pandemic in fact might have done the opposite: both when it came to the spread of COVID-19, as well as the greater impacts to health that the plastic industry produces.

It’s important to understand the economic benefits some experienced because of this push to bring back plastic bags, and to consider the fact that “public safety” was far from their primary motivation. Part of the shift was fueled by the recycling industry itself, already in crisis prior to the pandemic: “A company has to make more money on the resulting recycled material than what it costs to gather plastic waste and process it.”[XI] Since oil was so cheap at the time, it was cheaper to make new plastic than to recycle it, and because of COVID-19, more money was made by making new bags to keep up with demand, since many recyclers had to close because of lockdown restrictions tied to the pandemic.

The push toward increasing reliance on single-use plastic across the pandemic, while primarily propagated by the plastics industry, was also facilitated by the conversation around the important role that PPE played in keeping health workers and patients safe. We know that PPE is a necessary tool in combating the spread of transmissible virus, but the “conflation of single-use plastic along with PPE is interesting and hard to untangle in the collective commons. It’s the old ‘plastic is clean and transparent and safe’ argument, it’s hard to dismantle.”[XII]

While following conversations across Twitter in the summer of 2020, I wondered where this idea of “plastic = safe” came from and how it has become so engrained in our collective consciousness. Those within the environmental movement seemed to be talking about it too, despite the conversation gaining little traction online. This is from an article early on in the pandemic, in March 2020:

So why do we tend to think of plastic packaging as being sanitary when it’s not? Szaky traces that idea to the 1950s, when the oil industry first introduced disposable plastic packaging and goods. “Disposability brought about unparalleled affordability and convenience. Moving from a plate you had to wash—probably by hand, because there weren’t even dishwashers then—to a disposable plate you could throw away was massively liberating and also very cheap,” Szaky told Grist. “And I think what ended up happening is people got this misperception that wrapping something in plastic also made it more sanitary. [XIII]

The stories we tell ourselves are born out of convenience.

Now that I’ve been vaccinated and can venture out more into the world, I can’t help but ponder all of the plexiglass installed since the start of the pandemic. Presumably still in place to create a sense of security, the plastic remains despite the fact that, here in Alberta at the time of this writing, masks are barely present anymore.[XIV] At the start of the pandemic, a lot of stories moving across Twitter focused on the benefits of plastic as a barrier between us: as a way to remain safe from the virus while still being able to see and engage with one another. One of my findings online was the number of images with “plastic between people” that dominated feeds across May 2020.[XV]

This one image in particular struck me as interesting. The tagline, “Socializing in a Pandemic, Protected by Plastic,” sets up a narrative that plastic is the very thing that will keep us safe from the virus. Published May 2020, the story doesn’t reference either the NEJM study and its findings, or the overall impacts on health produced by the plastic industry.

Other stories focused on novel strategies businesses were experimenting with as they tried to reopen across the pandemic. While often somewhat humorous, expectations around businesses prioritizing plastic as part of their COVID strategy dominated. While these “lampshade-like shields” might not have caught on, they’re not that far off from the partial walls of plexi that ended up directing the response, and that remain present across businesses today.

Reports have come out since, confirming that these plastic shields in fact don’t work in stopping the transmission of COVID-19 or offer any safety against the virus. Perhaps more importantly, not one single study ever showed that they would, despite the fact that hundreds of millions of dollars were spent on the material in the USA alone: “‘We spent a lot of time and money focused on hygiene theater,’ said Allen, an indoor-air researcher. ‘The danger is that we didn’t deploy the resources to address the real threat, which was airborne transmission—both real dollars, but also time and attention.’ ‘The tide has turned,’ he said. ‘The problem is, it took a year.’”[XVI]

Of course, it takes time to understand a virus such as COVID-19, especially when the repercussions have unfolded so rapidly. I wonder though, now that the narrative has taken hold—and while plexiglass remains installed more than a year later, in businesses where masks remain highly contentious and, in a number of jurisdictions (including my own), no longer even required—how do we begin to shift the narrative?[XVII]

How do we get out of one storyline and shift into another?

Narratives around COVID-19 have no doubt been complicated by the invisibility of the virus: it’s difficult to explain complex ideas when their implications and repercussions aren’t readily observable. This invisibility factor is tied up with the complexity of plastics as well. From the ways that the industry pollutes our air, to the tiny microplastics at the heart of production: the lack of visibility surrounding our relationship to plastic influences the very way we consider its impacts. When you add the factor of convenience that plastic provides—the ease with which we incorporate plastic into our daily lives—it becomes easier to ignore the repercussions.

We’ve created this sense of unquestioning trust with plastic because it’s so closely associated with cleanliness and sterility. That is a benefit of plastic when it comes to medical use–for sure. But the stories we tell ourselves often classify all plastics as equal, ignoring its diverse degree of use, benefit, and even opportunity for recyclability. We ignore the impacts along with the potentials that might have been, had we only approached the industry with more scrutiny from the start. We know there are viable alternatives to plastics but, since we haven’t invested in them, they remain invisible to most.

We are now all made of plastic.

But how do we even have a conversation about it? How do we wade through all of the dis- and mis-information? How do we change the narrative and get to the cultural shift in perspective that we so desperately need?

This conversation is slowly moving back to centre stage. Across 2021, there has been a renewed energy around environmental issues at large, especially (quite problematically), as the impacts of climate change have come to be intimately felt across the Western world. Seeing images of pandemic waste piled up on beaches across the globe, and watching plastic waste accumulate as recycling plants shut down throughout the pandemic, helped illustrate our lack of ability to solve the plastics problem in the first place. Reading about the microplastics now known to be within the food we eat, in our rainwater and atmosphere, in our soil, and in our very bodies, is shifting the urgency of the conversation. [XVIII]

Perhaps, then, now is precisely the moment we need in order to shift the stories we’ve been telling ourselves about plastic and its impacts. One conversation that has started to gain traction across social media is the link between plastic pollution and COVID-19 itself, and the increased chances that populations (especially marginalized communities[XIX]) exposed to the direct impacts of the plastic industry have of being at risk for the virus. [XX]

I wonder what it might have looked like had we approached plastic use during COVID-19 from a different position, and in turn, what additional crises we have ultimately created in our handling of this one? The stories we tell ourselves now and the ways in which we visualize and make sense of this moment will shape our future. The question is: which story will dominate?

Endnotes

[I] E.L. Quarantelli, “Introduction,” What is a Disaster: A Dozen Perspectives on the Question (Routledge, 1998): xiv. Cited in Christina Battle, dissertation, University of Western Ontario.

[II] I’d like to explain a bit more about my interest on looking to Twitter for such insights. Monitoring online conversation is a great way to get a sense of how dominant cultural narratives take hold and persist. My focus is to look at Twitter as a space for shaping and spreading such dialogue, and while I recognize its limitations in being representative of the overall population, Twitter is known as a key location for journalists to engage with pressing issues, as well as a primary space for politicians to voice their platforms.

[III] Christina Battle, research report: Public perceptions of plastic during the start of COVID (May thru August 2020) as witnessed on Twitter; and thoughts on strategies for moving forward.

[IV] Battle, research report.

[V] Battle, research report.

[VIII] Neeltje van Doremalen et al. “Aerosol and Surface Stability of SARS-CoV-2 as Compared with SARS-CoV-1” New England Journal of Medicine, April 16, 2020, 382(16):1564-1567. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMc2004973. Across the Plastic Heart exhibition, the Synthetic Collective took care to incorporate non-plastic elements into the underlying structure of the exhibition. They looked to the infrastructure of the gallery itself as they balanced their emphasis on alternative materials along with COVID-19 safety protocols; the Art Museum’s door frames, for example, are made of copper.

[X] Battle, research report.

[XI] Battle, research report.

[XIV] As of early September, Alberta has reinstated their mask mandate, amidst ongoing criticisms of the province’s lack of COVID restrictions. See here for more.

[XV] Battle, research report.

[XVI] “Sales of plexiglass tripled to roughly $750 million in the U.S. after the pandemic hit, as offices, schools, restaurants and retail stores sought protection from the droplets that health authorities suspected were spreading the coronavirus. There was just one hitch. Not a single study has shown that the clear plastic barriers actually control the virus, said Joseph Allen of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.” See here for more.

[XVII] Also contributing to this narrative tangent is the fact that it took months for the WHO to recognize COVID-19 is transmitted through airborne aerosols despite pleas by scientists working on the subject, and Canada was even slower to accept the data as fact: only changing language regarding the transmission of the virus in November 2020, four months after the WHO guidelines were updated. See here for more. Alberta Health Services still hasn’t recognized the impact airborne aerosols have on transmitting the virus (https://www.albertahealthservices.ca/assets/info/ppih/if-ppih-ncov-2019-public-faq.pdf)

[XIX] There are many research sources citing the role that environmental racism plays in impacting communities unequally when it comes to polluting industries—see my project THE COMMUNITY IS NOT A HAPHAZARD COLLECTION OF INDIVIDUALS for more.

About

Christina Battle’s (Amiskwacîwâskahikan / Edmonton) artistic practice and research imagine how disaster could be utilized as a tactic for social change and as a tool for reimagining how dominant systems might radically shift. This work and research are situated around her recently completed PhD dissertation: Disaster as a Framework for Social Change: Searching for new patterns across plant ecology and online networks (2020).

Credits

Banner Image: Christina Battle, Notes to Self, video still, “progress isn’t always convenient,” 2014 – ongoing.

All images in essay courtesy of the artist.

Virtual Spotlight developed by Daniella Sanader, Content Curator, Plastic Heart: Surface All the Way Through.